5. Climate and Labor in La Gomera

It seemed that development was inevitable. This island was going to get developed and our brief was to put forward ways of working with locals as a sort of pump priming activity—as a kind of ginger group to try and suggest ways you could develop but preserve the spirit of the place, respond to the locale, if you like.

– Norman Foster, 1977 AIA Conference, London.

As the last of the projects commissioned by Norwegian shipping magnate Fred Olsen, Foster Associates’ La Gomera Regional Planning Study marks the end of a series of architecture-as-social-experiments performed by the firm in the 1970s. The study, by far the most radical of the Olsen projects, proposes methods for the ecological and economic rehabilitation of the island of La Gomera, one of the smaller inhabited Canaries. Focusing on green energy generation and material efficiency, the proposal aims to mobilize the inhabitants of the island as laborers reversing the negative effects on the island caused by exploitative lumber extraction, while at the same time developing the island for increased tourism managed by the Fred Olsen companies. As such, the project operated more as an exercise in systems management than traditional architectural design. The drawings made for the project can be roughly split into two groups, the ecological and the experiential. The team started by making a number of large-scale maps and diagrams showing the ideas and implications of their design as they affected the entire island. From solar farms to water desalination techniques, the team took a high-tech, prefabricated approach to restoring the ecosystem to a pre-Columbian state. On the other hand, the experiential drawings show tourists engaging in the usual activities of hiking, beach-going, and swimming at the same time that the inhabitants of the island labor to create “low-rise high-density,” vernacular-based hotel units and install the green-technology. Through these drawings the Foster Associates team proposes to solve two problems, the environmental problem and the surplus labor “problem.” Similarly, these images also show the two-scaled approach taken by the team in their proposal, that is, the scale of the territory and the scale of the body.

In his 2014 essay “Scale Critique for the Anthropocene,” Derek Woods defines scale variance as a mode of analysis that accepts and highlights the necessary disjunctions between scales. He writes, “scale variance means that the observation and the operation of systems are subject to different constraints at different scales due to real discontinuities.” In the case of the La Gomera project, scale variance opens up the possibility of understanding the multiplicity of factors that make up Foster’s proposal as necessarily disjunctive and open to their own praise and critique. While the large-scale ecological ideals of the project may be praise worthy, and even a bit ahead of their time, the smaller pieces of the proposal should simultaneously be considered for their own individual qualities and relationships.

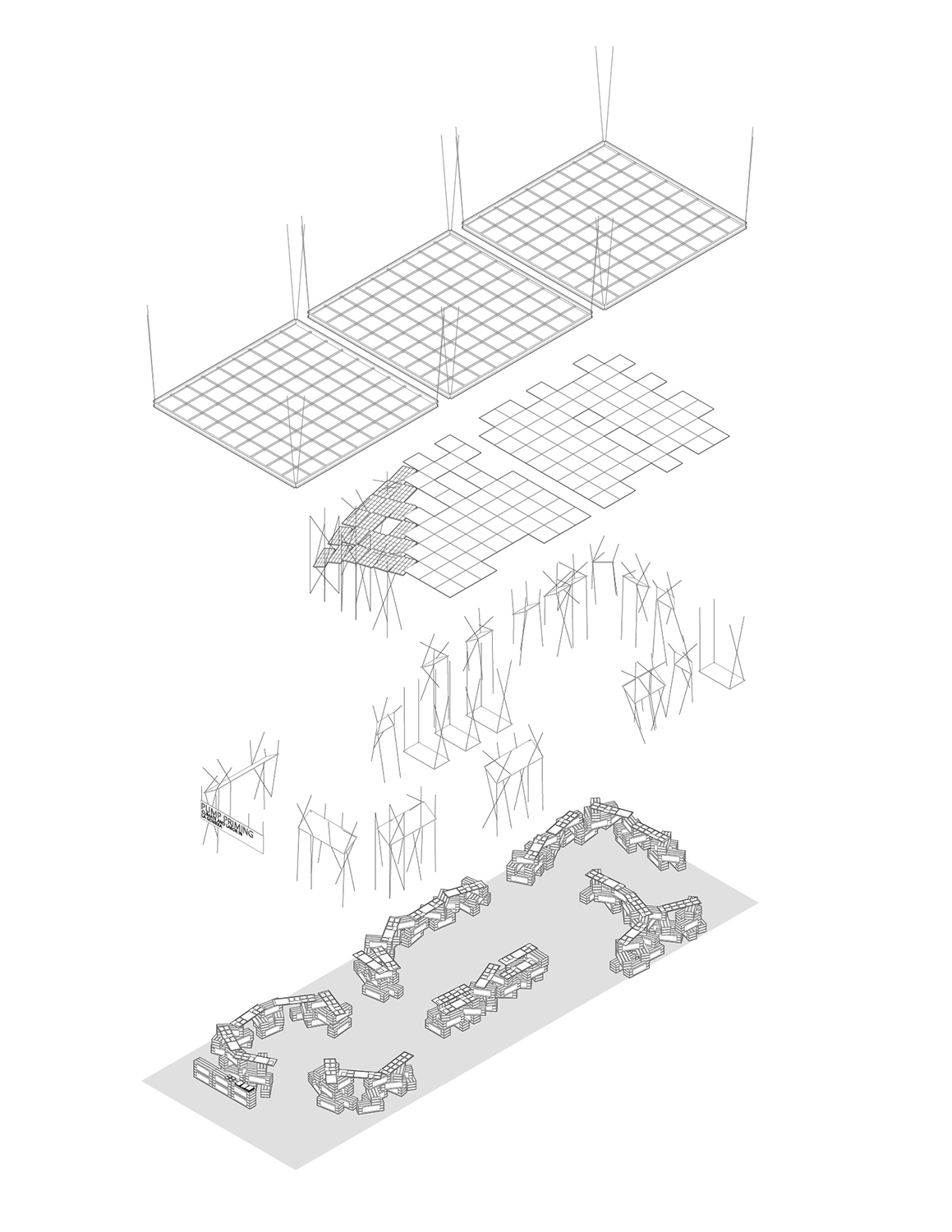

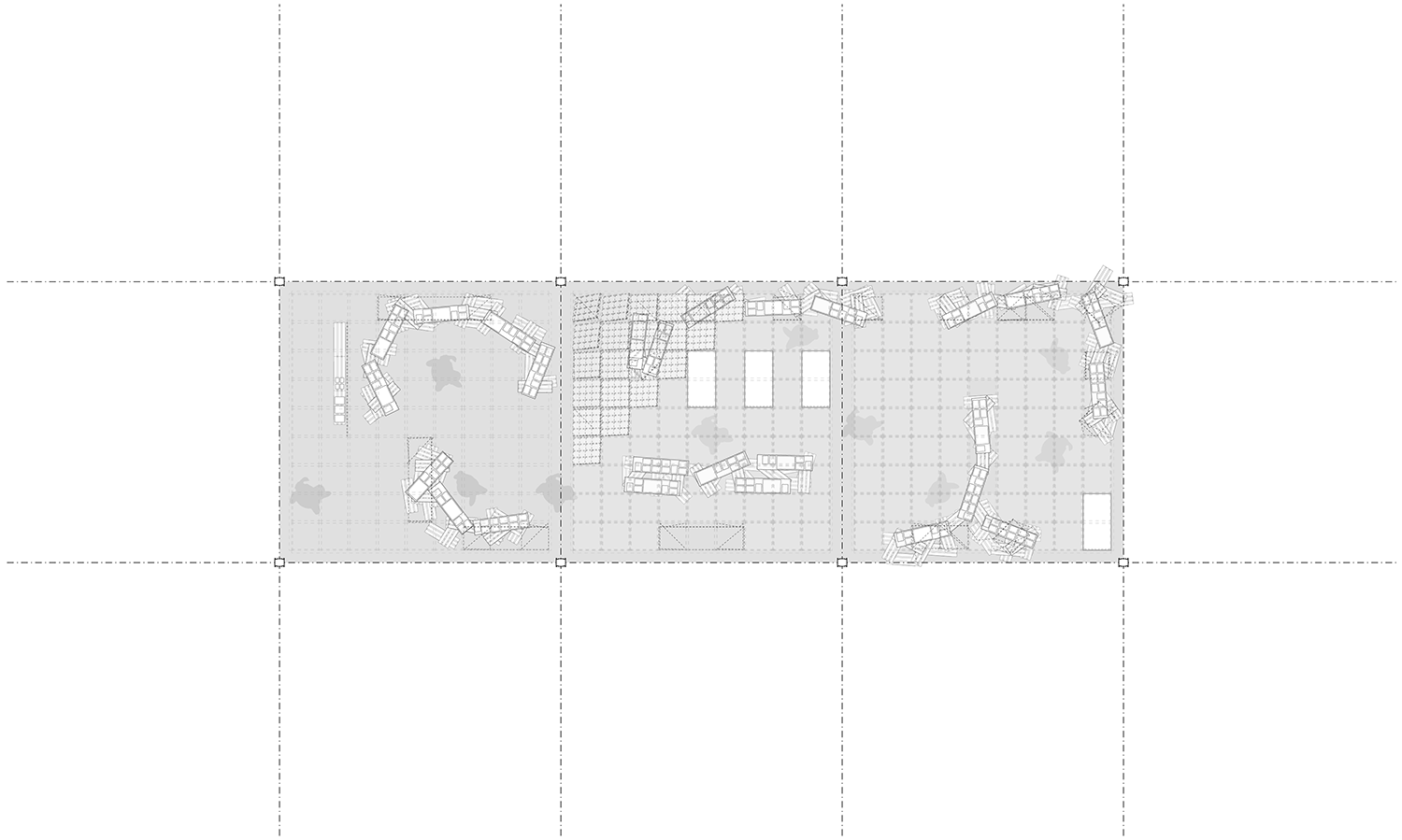

The exhibition aims to tease out these smaller aspects of the project through a collection of drawings made for the proposal, records of lectures and texts about the project, and, most importantly, through a series of previously unpublished photographs taken by the Foster Associates team while on a site visit in the 1970s. These materials are organized to show the differences in scale inherent in the project through the relationship of the hanging materials to those rising from the floor, relate to the historic labor conditions of the island as well as those proposed by Foster and Olsen through the metal roof structure and the counteracting banana boxes, and to encourage the visitors to ask questions both about the project itself and about our larger attitude toward climate and labor. More specifically, the exhibition asks its visitors to weigh the effects of a changing climate with the self-determination of an island population.

What was clear to the Foster Associates team in the case of La Gomera, and has been made increasingly clear over the 40 years since the project was shelved, is the need to adapt both technology and the organization of society to the changing climate. It is also clear that that change will require a mountain of labor both physical and intellectual, and it is the organization of that labor that the Foster Associates team proposed in the ‘70s. It is here that the photographs and drawings become key to the exhibition. The most important question that the visitors to the exhibition can ask is “who?” Who does the manual labor? Who does the intellectual labor? And, critically, who stands to gain the most from those labors?

– Norman Foster, 1977 AIA Conference, London.

As the last of the projects commissioned by Norwegian shipping magnate Fred Olsen, Foster Associates’ La Gomera Regional Planning Study marks the end of a series of architecture-as-social-experiments performed by the firm in the 1970s. The study, by far the most radical of the Olsen projects, proposes methods for the ecological and economic rehabilitation of the island of La Gomera, one of the smaller inhabited Canaries. Focusing on green energy generation and material efficiency, the proposal aims to mobilize the inhabitants of the island as laborers reversing the negative effects on the island caused by exploitative lumber extraction, while at the same time developing the island for increased tourism managed by the Fred Olsen companies. As such, the project operated more as an exercise in systems management than traditional architectural design. The drawings made for the project can be roughly split into two groups, the ecological and the experiential. The team started by making a number of large-scale maps and diagrams showing the ideas and implications of their design as they affected the entire island. From solar farms to water desalination techniques, the team took a high-tech, prefabricated approach to restoring the ecosystem to a pre-Columbian state. On the other hand, the experiential drawings show tourists engaging in the usual activities of hiking, beach-going, and swimming at the same time that the inhabitants of the island labor to create “low-rise high-density,” vernacular-based hotel units and install the green-technology. Through these drawings the Foster Associates team proposes to solve two problems, the environmental problem and the surplus labor “problem.” Similarly, these images also show the two-scaled approach taken by the team in their proposal, that is, the scale of the territory and the scale of the body.

In his 2014 essay “Scale Critique for the Anthropocene,” Derek Woods defines scale variance as a mode of analysis that accepts and highlights the necessary disjunctions between scales. He writes, “scale variance means that the observation and the operation of systems are subject to different constraints at different scales due to real discontinuities.” In the case of the La Gomera project, scale variance opens up the possibility of understanding the multiplicity of factors that make up Foster’s proposal as necessarily disjunctive and open to their own praise and critique. While the large-scale ecological ideals of the project may be praise worthy, and even a bit ahead of their time, the smaller pieces of the proposal should simultaneously be considered for their own individual qualities and relationships.

The exhibition aims to tease out these smaller aspects of the project through a collection of drawings made for the proposal, records of lectures and texts about the project, and, most importantly, through a series of previously unpublished photographs taken by the Foster Associates team while on a site visit in the 1970s. These materials are organized to show the differences in scale inherent in the project through the relationship of the hanging materials to those rising from the floor, relate to the historic labor conditions of the island as well as those proposed by Foster and Olsen through the metal roof structure and the counteracting banana boxes, and to encourage the visitors to ask questions both about the project itself and about our larger attitude toward climate and labor. More specifically, the exhibition asks its visitors to weigh the effects of a changing climate with the self-determination of an island population.

What was clear to the Foster Associates team in the case of La Gomera, and has been made increasingly clear over the 40 years since the project was shelved, is the need to adapt both technology and the organization of society to the changing climate. It is also clear that that change will require a mountain of labor both physical and intellectual, and it is the organization of that labor that the Foster Associates team proposed in the ‘70s. It is here that the photographs and drawings become key to the exhibition. The most important question that the visitors to the exhibition can ask is “who?” Who does the manual labor? Who does the intellectual labor? And, critically, who stands to gain the most from those labors?